SERIE:

“s u k i”

Paris, 2018

TECHNIQUE:

photomontage & collage,

pigment printing process. baryta paper

photos-numbered (Limited Edition)

WOODEN FRAMED

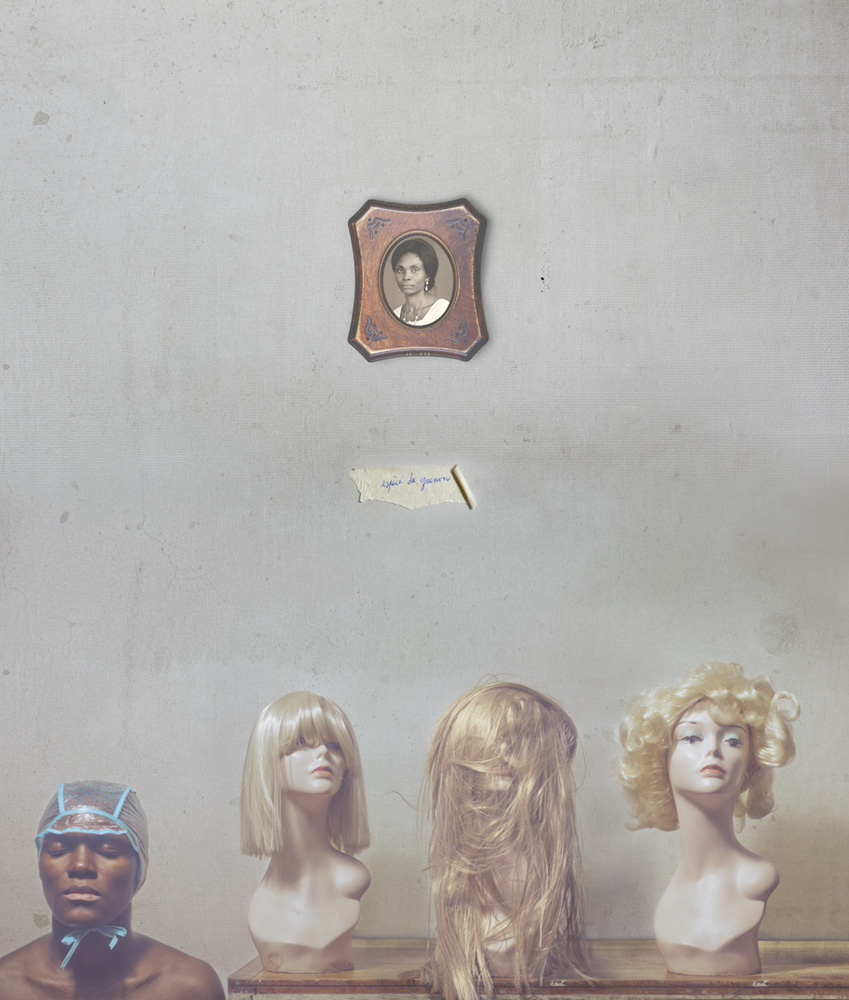

« Mwana Mundele Suki Lala »

- The little white boy’s hair sleeps -

{in lingala, my mother tongue}

french version︎

For many years, back in Kinshasa, I have said this same sentence while looking at the hair of my fellow European friends at school. «The little white boy’s hair sleeps» Smooth, malleable, when mine had to be tamed…

Straightening, plaiting, relaxing… :

The typical routine of most African women around the world. A habit so common and widespread, that I’ve always considered normal myself. Just as we had different clothes for different occasions, it was usual to change hairstyles for funerals, baptisms, weddings, births, birthdays or parties was usual. And it was so natural that it was going as far as changing the texture of the hair, its colour and nature on a regular basis. So was seeing my grandmother put on her wedding or funeral wig and hiding her beautiful hair under a synthetic apparel to assert even more her beauty.

All that to be « presentable » and comply with beauty standards that Africa has inherited from the occidental world. This ancient habit had appeared in the African continent under slavery and went on after colonialism. With hairpieces and wigs as their prerogatives, white people determined social rank and beauty standards. And as time passed, those aesthetic codes ended up crushing our own leaving room for an unattainable ideal. Long and smooth, coloured blond, brown, auburn or ginger… Anything but the curly, fuzzy, uncontrollable hair consciously or unconsciously rejected by African women.

And I was no exception.

It all began when I was 10. The age when feminine ideal requires all Congolese girls to relax their hair, like a rite of passage, the entry to the adult world. Despite the constraints and risk of loosing hair, this ceremonial came into my life, only to be questioned 20 years later.

Giving up into laziness and tiredness,

I thought to myself:

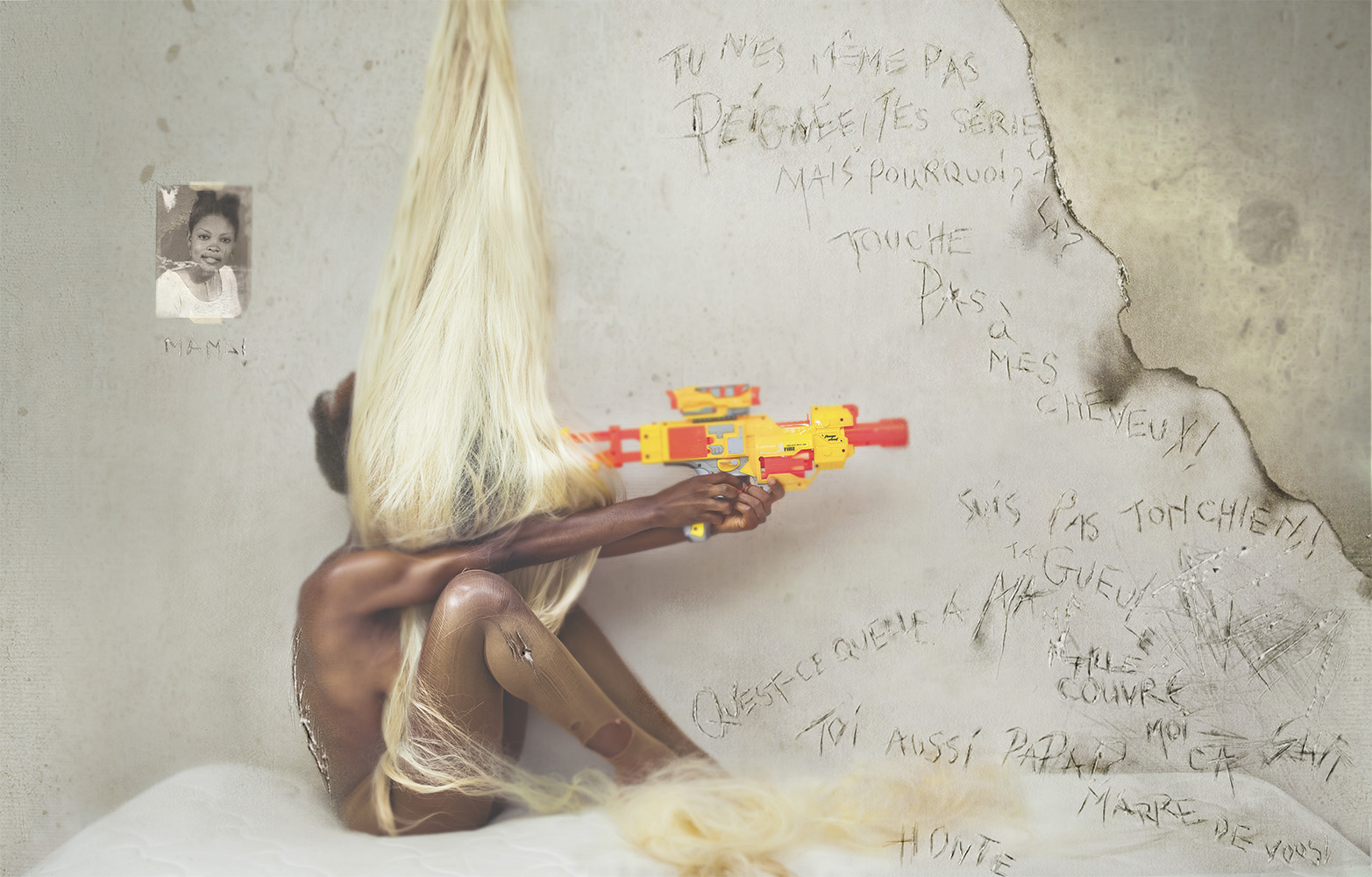

Why should I be a replica of white standards?

This psychological introspection, materialized through the banishment of the relaxer from my beauty routine and soon after, began a long struggle against my own perceptions.

From the «Your hair is untidy!» of anxious parents to the aggressive «Monkey!», an African waitress has once thrown at me…

I soon started to face the first judgments, the first remarks that were finally just the mirror of my own perception of beauty.

For I, was never even able to find beauty in my own fuzzy hair.

The path I was walking on did not seem peaceful.

On this very long, slow and hard path of self-acceptation, a strong desire to own my hair back arose. But history was and is still present, very much part of my life and my beauty routine.

Denying the existence of these habits is vain.

SUKI illustrates the struggles and the conflicts of this journey. By confronting each beauty standard with their origins, showing the techniques created to enslave Africa through hair, the photographic series reveal a new and emancipated Africa. That same Africa torn between today’s imposed culture, reappropriation of its own

and firm determination to build a future

SUKI, like hair in lingala, SUKI because I am from Congo, SUKI as an antidote, an escape. My escape.

I soon started to face the first judgments, the first remarks that were finally just the mirror of my own perception of beauty.

For I, was never even able to find beauty in my own fuzzy hair.

The path I was walking on did not seem peaceful.

On this very long, slow and hard path of self-acceptation, a strong desire to own my hair back arose. But history was and is still present, very much part of my life and my beauty routine.

Denying the existence of these habits is vain.

SUKI illustrates the struggles and the conflicts of this journey. By confronting each beauty standard with their origins, showing the techniques created to enslave Africa through hair, the photographic series reveal a new and emancipated Africa. That same Africa torn between today’s imposed culture, reappropriation of its own

and firm determination to build a future

SUKI, like hair in lingala, SUKI because I am from Congo, SUKI as an antidote, an escape. My escape.